One hundred years ago, forests looked very different than they do today. Before 1900, “one…

By Emma Childs, TLC Working Lands Manager

Given my preference for dark over milk chocolate and my apathy towards stuffed bears, Valentine’s Day does not perch at the top of my ‘favorite holidays’ list. However, the last two or three Februarys have still been the most romantic of my life. I’ve spent many dusk hours at the edges of forests and scrubby fields, staring across the dimming landscape, listening for an elusive, buzzing peent call in the winter weeks that follow Imbolc (the halfway point between the winter solstice and spring equinox). When lucky, my ears will catch it as the hues of the horizon deepen to a bluebird’s breast merging of orange and peach. If I’m even luckier, my eyes will also snag on a whirling outline in the sky, a fluttering bird carrying out what has been deemed an iconic “sky dance” by conservationists across the country.

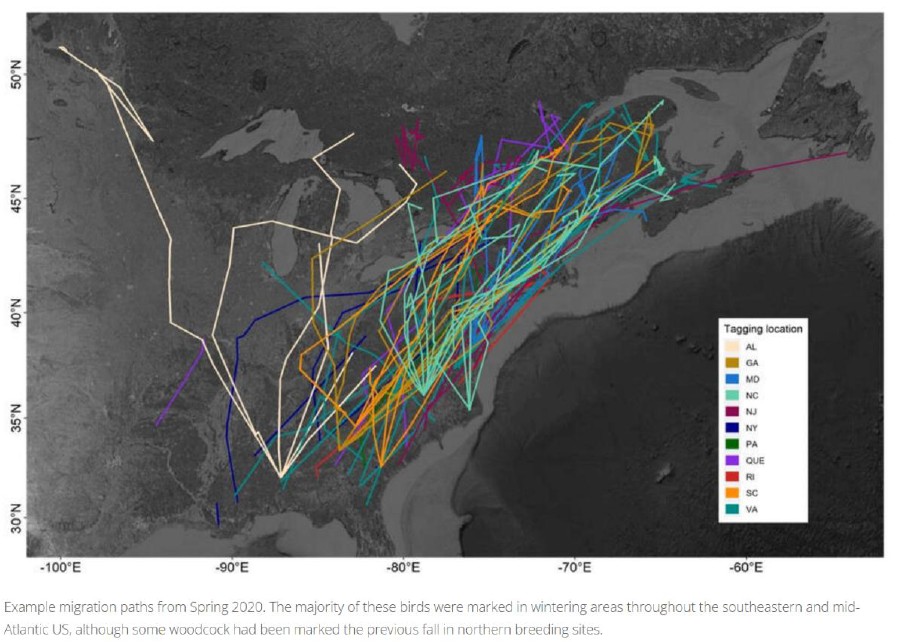

Scolopax minor, otherwise known as the American Woodcock, or more affectionately as the timberdoodle, mudsnipe, or bogsucker, graces those of us in the Piedmont with its quirky ritual mating dance during early February, as part of its migratory stopover. Woodcocks live in the forested Triangle region year-round, but the individuals passing through on their way back north cause the local population numbers to swell at this time of year. I like to think of these stopover sites as sanctuaries for weary avian journeyers, pausing to rest, eat, and for the males to practice their courtship displays. If you are a frequenter of TLC preserves, you may have heard or seen these unique birds at Horton Grove or Brumley.

A shorebird that resides nowhere near the beach, woodcocks like their feet to be wet, but not submerged in standing water like other snipe species. They are mostly nocturnal mottled ground-dwellers and ground nesters that search the forest floor for earthworms and other small insects, probing with their long beaks through the leaf litter in young, early successional forests and shrubby field habitat. The very scrubby fields where I find myself in waning light, transfixed and hopeful, during the weeks before Valentine’s Day.

The nasal-y peent that initiates their sky dance can carry several hundred yards, and I’m always thrilled when I hear it, knowing the bird is vaguely near. But prior to the peent, male woodcocks let out a much softer, two-syllable gurgling note known as a tuko that is only audible about 10 yards or less from the bird. The woodcock then launches from the ground, making a wide upward spiral, twittering his wings while rising higher in the sky (one could easily confuse them with bats at first blush). Once he reaches nearly 300 feet, he will zigzag his way back to Earth, chirping the whole way before landing silently near a female if she is around. This ritual can continue multiple times through the evening until a successful mating.

Sky dance aside, the woodcock has multiple notable characteristics that might capture even a non-birder’s attention. Their brain is upside down within their skull compared to other birds, and their eyes’ position allows a 360-degree horizontal plane of vision and better advance warning of predators. Their prehensile beak tip allows the beak to open for worms even when stuck deep in the ground. What has perhaps brought the woodcock true internet fame is their propensity to rock back and forth intermittently while walking, a move that should likely be integrated at your next dance party. Scientists are not exactly sure why the birds move and groove in this manner, but two main theories prevail. The first is that they are feeling for earthworms and other insects on or under the soil surface. The second is that they know they are being watched, and like a white-tailed deer, it is a signal of acknowledgement and potential danger.

Given woodcocks’ preference for shrubby patches of young forest or overgrown farm fields with high stem counts, their food and habitat needs have led to “spirited debate” across the ornithology, ecology, and forestry communities about the role that active forest management should play in supporting woodcock populations. Thankfully, foresters, hunters, and birders across the Southeast share a fondness for the timberdoodle and are banding together to ensure woodcocks have space to thrive for many years to come. This is where TLC’s commitment to providing diverse wildlife habitat for a wide variety of species is critically important, and the early successional forest patches across our preserves provide these conditions.

So, this Valentine’s Day, instead of a candlelit dinner, consider snagging a beloved friend, family member, or neighbor, and your tried-and-true binoculars and head out to a TLC trail to look for local artist Courtney Pernell’s handmade pottery “love birds” or the American Woodcock’s sky dance…you just might lose your heart to these amazing creatures!

*Note – While TLC does encourage looking for woodcocks at our preserves, all preserves close at sundown, and we ask visitors to respect this rule for everyone’s well-being and safety.