By Ron Gallagher

The highly successful and innovative Upper Neuse Clean Water Initiative, already well into its teenage years, is about to get a sibling. This fall, TLC and multiple partners unveil the Jordan Lake Watershed Conservation Strategy that will be a component of a new water-protection effort called the Jordan Lake One-Water initiative (JLOW).

The highly successful and innovative Upper Neuse Clean Water Initiative, already well into its teenage years, is about to get a sibling. This fall, TLC and multiple partners unveil the Jordan Lake Watershed Conservation Strategy that will be a component of a new water-protection effort called the Jordan Lake One-Water initiative (JLOW).

Forging JLOW has brought together local governments in the Triangle and Triad, state water-quality officials, and multiple conservation and watershed-protection groups. All are looking for ways to reduce nutrients and pollution in the Haw River and the 14,000- acre Jordan Lake that was created when the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers dammed the Haw near its confluence with the Deep River in 1973. The same year, the North Carolina Environmental Management Commission declared the reservoir as “Nutrient-Sensitive Waters” — but Jordan Lake has yet to conform to U.S. Environmental Protection Agency standards for nutrient pollution.

JLOW (pronounced JAY-low) grew out of a 2017 summit meeting about water quality in Jordan Lake. The initiative is administered by the Triangle J Council of Governments (TJCOG) with assistance from the Piedmont Triad Regional Council (PTRC) and the Jordan Lake One Water Advisory Committee.

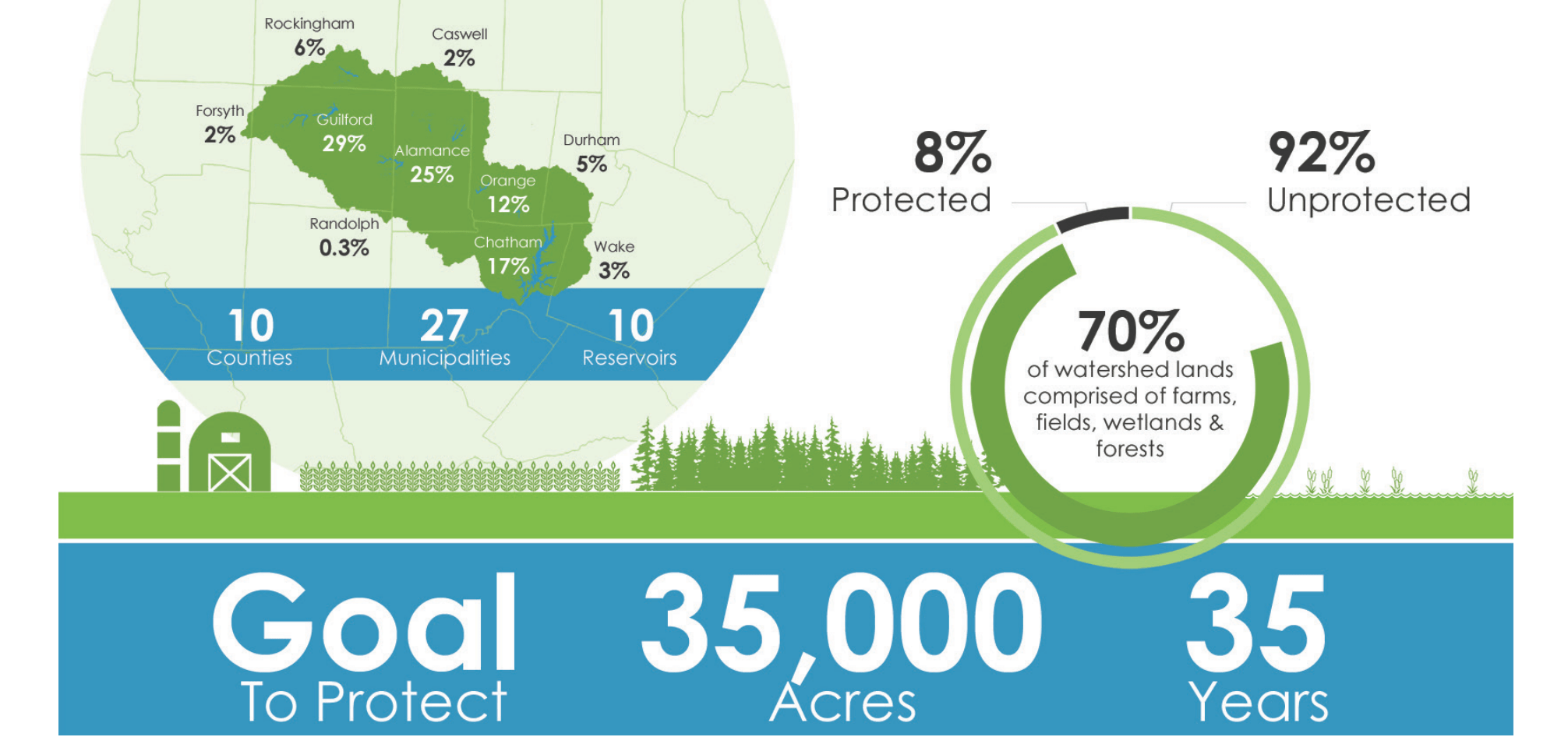

The goal of JLOW, as stated in the conservation strategy, is “to develop and implement an integrated watershed management strategy” for the 1,687-square-mile watershed that reaches into 10 counties and feeds 10 reservoirs accessed by 26 municipal water-supply systems.

TLC’s efforts, led by Senior Associate Director of Conservation, Leigh Ann Hammerbacher, and other partners, have created a strategy that hews to JLOW’s six goals for a unified effort to improve Jordan Lake’s water quality:

1. Solve regional watershed issues beyond the capacity of any one stakeholder

2. Draw on the leadership of elected officials and other champions of the group to make change

3. Work closely with state regulators to develop an effective, integrated watershed policy framework

4. Increase access to funding opportunities for watershed improvements

5. Establish and develop partnerships and trust

6. Share knowledge, resources, and experience among disparate stakeholder groups

Drawing on TLC’s experience and strength

The best way to keep harmful nutrients and sediment out of drinking-water systems is to start where the pollution starts and do everything possible to protect upstream lands. These woods and farms serve as buffers and filters for surface and groundwater that will become drinking water for as many as 700,000 people in the watershed.

So far, about 8 percent of the Jordan Lake watershed – approximately 88,000 acres out of more than 1 million – is protected. JLOW has a big challenge, but protecting land is where TLC’s decades of experience can contribute the most. The Upper Neuse Clean Water Initiative (also known as the Raleigh Watershed Protection Program) is the successful model that the JLOW conservation strategy aims to replicate across multiple jurisdictions.

Over the course of 14 years, TLC and other partners working in the Upper Neuse River put together and implemented a conservation plan that centers on lands where conservation can have the biggest impact on water quality in the 770-square-mile Upper Neuse watershed.

That plan used the best available science and geographic data to focus land protection priorities. The City of Raleigh, drawing water from the Falls Lake reservoir, has a big stake in the quality of its water and has supported the strategy vigorously.

Perhaps the best evidence that saving land to save water makes great sense is that for every dollar that the city contributes, the initiative has been able to generate an additional $7 for land acquisition and protection. Customers pay a 15-cent fee for every 1,000 gallons of water used in the city and surrounding communities.

So far, the Upper Neuse initiative has protected over 10,000 acres of land in the Falls Lake watershed. That land involves 114 properties and has provided buffers along 111 miles of streams.

Building on the success of the Upper Neuse program, the JLOW partners have set a goal of protecting 35,000 acres over the next 35 years based on assessments of funding opportunities and land that could be available for conservation. That is about 5 percent of the eligible land that the partners identified in the Jordan Lake Watershed.

As the conservation strategy puts it, the 35,000-acre goal “would provide tangible water-quality benefits within the watershed and is a feasible target within a voluntary landowner, market-driven system.” With additional state and local funding sources and potential credits for conservation, TLC and partners think they could easily double or triple this goal.

“Broad support from stakeholders in the watershed will help turn this ambitious vision into a reality,” emphasized Sandy Sweitzer, TLC’s Executive Director.

Working with data that TLC and others pulled together into a GIS-based map of the Jordan Lake watershed, the process of identifying lands for conservation and weighting priorities culminated in a March 27 meeting of 60 stakeholders at the Impact Alamance Center in Burlington.

That report stood on the shoulders of work that has guided the Upper Neuse efforts.

In 2018 and earlier this year, the team creating the model for Jordan Lake met with individual stakeholders, local officials who operate the water-supply systems, and the larger partnership group to get feedback that went into refining the model. After collecting inputs, the model was used to show “priority” parcels in the watershed. Those parcels scored higher than the median score of 47.2 out of 100 and were at least 10 acres. With those criteria, the model identified more than 10,000 parcels that comprise over 385,000 acres in the watershed. Those, the report says, would be parcels eligible for conservation if a fund were created to fuel the Jordan Lake program.

The Jordan Lake Strategy is part of a much larger project: by January 2020, the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality’s Division of Water Quality is req uired by law to begin a process that will lead to reviewing conditions in Jordan Lake and setting water standards. It is a process known as readoption.

uired by law to begin a process that will lead to reviewing conditions in Jordan Lake and setting water standards. It is a process known as readoption.

At a June 26 JLOW meeting in Mebane, Patrick Beggs, a water-quality specialist at DEQ, made it clear that the conservation strategy and other JLOW efforts can be part of the state’s wider plan for the lake. Because DEQ is, in effect, taking a whole new look at the lake’s future, “Everything is on the table,” Beggs told the group.

The JLOW model can feed into what Beggs called a policy collaborative for Jordan Lake standard-setting.

“I’m sure,” Beggs said, “we can come up with something far superior” to any past efforts. “And, maybe nowhere in the world has this been done for an area this size.”