By Laura Warman, Grants Manager

This month we are highlighting woodpeckers – a group of fascinating birds with amazing adaptations that allow them to do things that other animals can’t.

The word “woodpecker” tends to invoke an image of a black and white bird with a red head (possibly in cartoon form) that uses a long beak to poke holes in tall trees, but woodpeckers come in a surprising range of colors, shapes, and sizes. There are roughly 250 species of woodpeckers across the planet, from the higher latitudes to the tropics (but not in Oceania). Some woodpeckers, like the Gila woodpecker of the US Southwest and Northern Mexico, have specialized in living in distinctly tree-less environments, and make their nests in saguaro cacti.

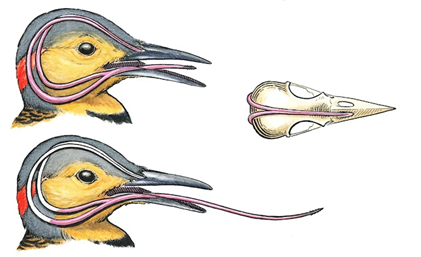

So how do woodpeckers manage to hammer their heads at high speeds and with a lot of force into trees, without giving themselves brain injuries (and constant headaches)? The answer is still not entirely clear, although scientists have spent a lot of time looking into this- which has led to advances in shock-absorbing materials (and bike helmets!). It may be that the size of their brains is what protects them, but we also know that they have specialized structures in their heads, such as the hyoid apparatus which are probably coming into play. The hyoid apparatus is a long structure that involves bones, muscles, and cartilage- in woodpeckers it is anchored at the base of their nostrils, and then splits into two halves that go up over and around woodpecker’s skulls, and then come up from the base and attach to their tongue muscles. It is thought that when these muscles contract, the hyoid apparatus can act as a safety belt for the woodpeckers’ brains.

Not only are woodpecker tongues very long, but they are also specialized in diverse ways that help different species get their food. Most woodpeckers’ diets include a lot of insects, and the barbs at the end of their tongues help them scrape insects out of the holes they carve in trees. In the case of sapsuckers, these barbs are bristle-like and help the birds get to the sap they feed on. Meanwhile, flickers, who specialize in eating ants, have more flattened tongues and sticky saliva. Most of the woodpeckers in North Carolina eat a mixture of ants, termites, beetle larvae, caterpillars, flying insects, berries and acorns from oaks, sumac, holly, dogwoods, and native cherries. While sapsuckers can visit orchards to sample fruit, most woodpeckers are an important control for bark beetles as well as caterpillars and other insects in orchards.

Unlike songbirds, who sing long complicated melodies, woodpecker calls are fairly simple and repetitive. However, they also communicate using “drumming”- the sound patterns made when they hammer their bills on wood. Drumming can be very distinctive between species, and woodpeckers us it to find mates and also as an indicator of territory boundaries. A recent study found that the same part of the brain that helps songbirds learn their songs is involved in drumming patterns in woodpeckers.

Woodpeckers can be very long lived birds- with individuals recaptured 10 to 12 years after they were originally banded. While most live solitary lives, some like Pileated woodpeckers, appear to mate for life, and other like the acorn woodpeckers of the Western U.S. live in larger groups. Most woodpeckers nest in cavities they either made or find in trees, and in many species the males are responsible for both making the nest and incubating the eggs at night. Because they use cavities in old trees, which are a rare and valuable resource in a forest, many species of woodpeckers are particularly threatened by habitat loss and fragmentation, loss of old trees, loss of fire on the landscape and the introductions of invasive species like starlings, who steal nests from woodpeckers.

Many species of woodpeckers will come to backyard birdfeeders, and nest in nest boxes, but if you want to improve habitat for woodpeckers around you, bes sure to leave old trees and stumps. Also keep in mind that if they are making holes in your house, it is likely they are letting you know there are bugs that they eat in the wood. These are the woodpeckers you are most likely to see in the Triangle:

Pileated Woodpeckers (Dryocopus pileatus) are unmistakable large woodpeckers- nearly as large as crows! These charismatic percussionists are considered the third largest species of living woodpeckers in the world, and belong to a genus of large woodpeckers that live around the world (one of its Eurasian cousins, Dryocopus martius is considered the second largest). The males incubate eggs in cavities in larger trees, and while you might see these woodpeckers at a feeder, you’re more likely to find them in the woods. Keep an eye out for the square holes they make in trees, and an ear out for their loud calls and drumming.

Northern Flickers (Colaptes auratus) break all the expected woodpecker guidelines. Rather than black and white, these large woodpeckers have colorful plumage ranging from warm reddish-brown to shades of brown and gray, with a black collar on their chest and spots covering their front. You are more likely to find one on the ground looking for ants and beetles to eat than making holes high up in the trees. Flickers are also one of the few migrating species of woodpecker, even though there are also resident populations that stay put throughout the year.

Red-bellied Woodpeckers (Melanerpes carolinus). Despite their name, what you will first notice is that they have a bright red head, pale undersides, and a black and white striped back—although if you look closely you might be able to see a vague reddish patch on their bellies. During the warmer months, up to half of a Red-bellied woodpeckers’ diet can be made up of plant matter. This species is found across the East Coast, and their range is expanding further into Canada, possibly because they are regular visitors to bird feeders.

Hairy and Downy woodpeckers look remarkably similar. Despite common instructions to look at relative beak length (longer for Hairy Woodpeckers) or very discreet differences in their tails and shoulders (a lighter tail feather here, or a darker mark there)- the easiest way to tell them apart is their size. Once you’ve seen these birds side-by-side, you realize just how much bigger Hairy Woodpeckers are than their Downy counterparts. Downy Woodpeckers (Dryobates pubescens) are the smallest woodpeckers in the US and Canada, whereas Hairy Woodpeckers (Dryobates villosus) are similar in size to Red-bellied Woodpeckers (although I always think that attitude makes Red-bellied woodpeckers seem even bigger). Downy Woodpeckers are common visitors at feeders and form part of mixed feeding flocks including titmice and chickadees, whereas Hairy woodpeckers can be shier.

As their name suggests, the diet of Yellow-bellied Sapsuckers (Sphyrapicus varius) is heavily centered on sap that they tap from “wells” they make in trees. They make neat rows of holes across tree trunks and maintain these wells to keep sap flowing over time. They are a migratory species and can be found overwintering in Central America and breeding as far North as Alaska.

Once you see a Red-headed Woodpecker (Melanerpes erythrocephalus), you can understand why they beat the Red-bellies to the name. The heads of both males and females are covered in deep red feathers that contrast with their black and white bodies. These birds like open woodlands, and unlike most other woodpeckers, they catch insects on the wing- much like flycatchers do. While not migratory, they are a nomadic species that moves around on the landscape over time, and so you might not see them often at the same spot. Unfortunately, their populations are decreasing due to loss of habitat, particularly bottomland forests, and they are also affected by loss of fire on the landscape.

Lastly, although you are unlikely to see them in the Triangle, Red-cockaded Woodpeckers (Dryobates borealis) are very cool birds that live exclusively in open pine woodlands of the Southeastern US, particularly in old longleaf pine stands with very little understory. These woodpeckers live in small family groups and are cooperative breeders- that is, each breeding pair lives with a group of younger (usually male) birds who help raise the chicks. Due primarily to habitat loss (because of deforestation, habitat fragmentation and fire suppression), they were listed as Endangered in 1970 and they are currently considered threatened. If you want to see these birds in NC they are now found mainly along the coast and in the Sandhills region.

Help us keep woodpecker habitat healthy by becoming a TLC member and/or volunteering with us at our Preserves! Winter is a great time to see woodpeckers, so make the most of TLC and come out to hike and look for them.

This month’s species spotlight is brought to you by a TLC staff request, illustrated with this lovely drawing of a red-headed woodpecker. If you have a request for a species you’d like us to spotlight, fill out the form below!